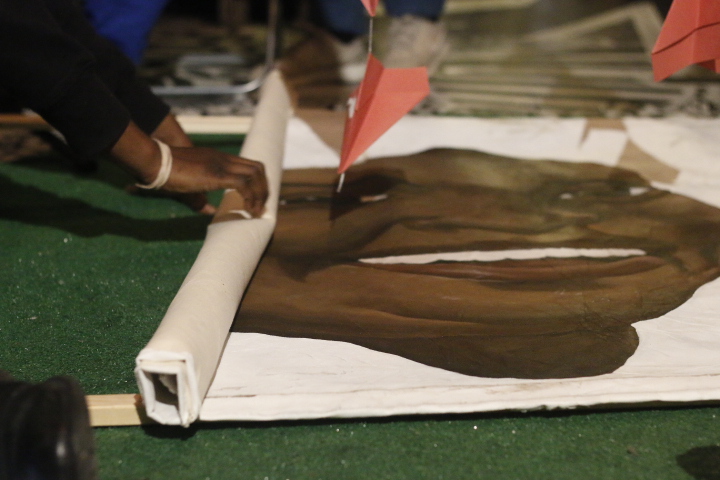

Silhouettes of Ashley Shey (left) and Yacine Fall (right) during performance piece “Wherefore art thou, Olympus?” by Maps Glover at the 15th annual Transformer Auction Party. Photograph by Maxwell Young

Since mid-September, Maps Glover and Uptown Art House have been curating programs and experiences in conjunction with Transformer Gallery, a non-profit art studio in Logan Circle amplifying the work of burgeoning artists around the Washington, D.C. creative ecosystem. What began as a six-week exhibition dubbed What We Leave Behind: In the Name of Art, culminated in a final performance during Transformer’s 15th annual auction party on Saturday night.

"Wherefore art thou, Olympus?” was an exploratory piece considering the spectrum of value civilization has placed on black bodies and images. More specifically, “It was about reaching for an idealized sense of acceptance from white society,” said Jamal Gray, who was a part of the performing troupe.

Glover and Gray along with Yacine Fall, Ra Nubi, Ashley Shey, Sifu Sun, and Hipster Woods were clad in dark tunics and skirts, enshrouded by masks and headdresses made of metal wire. Fastened to a chain that ascended the temple-like steps of George Washington University’s Corcoran School of Art, the sextet moved up and down the grand staircase in tandem with one another, striking poses, tying one another up, and manipulating the chain with their bodies. It was a stark contrast to a predominantly white audience in a predominantly white space raising questions of what this performance was about.

Figuratively, this group of artists who debuted together in Uptown Art House’s audiovisual experience at The Kennedy Center last March, The Landing, transformed themselves into “black deities,” Glover explained, recounting his performance. Coupled with the neoclassical architecture of the Corcoran building, the piece alluded to the idea of white acceptance mentioned by Gray because of the white connotations associated with western mythology. Gods and goddesses represent the epitome of social constructs like beauty, power, and knowledge that black people have been historically disenfranchised from, whether through slavery, racism, or the erasure from history. It’s as if the masks and chains worn by the troupe symbolized the conformity and constraining that happens to black bodies as they navigate this white, western world.

“We can’t exist in this paradigm of America and not address it,” Gray said.

Oscar Cole pictured far right and members of Millennium Arts Salon. Polaroids by Maxwell Young

Oscar Cole, however, pictured on the far right, had a different perspective of the performance he witnessed at the auction party, telling me disapprovingly, “We must be aware of the images we project.”

Cole, who was sitting with several elder African American members of the Millennium Arts Salon, an organization promoting cultural literacy through art programming, was generations removed from the freedom of expression that he saw Saturday night. Born in 1943 in North Carolina, Cole fought for racial equality, participating in sit-ins. Cole is also an alumnus of Howard University and he also holds a PHD in psychology from the University of Michigan. He could not remove “Wherefore art thou, Olympus?” from his personal context in America—one of long-term resistance to oppression. He saw the six black bodies on the steps and he saw the chains they were bounded by and he was reminded of slavery, a topic in 1943 that could have close ties to his ancestral history. And in 2018 with President Trump condoning images of prejudice, Cole saw an insensitivity to the current times and intolerance minorities experience.

“We’re all slaves to something,” Ra Nubi told me after I shared with her Oscar’s story. “The idea of being a black woman, there’s a type of inescapable truth to what it is to be here and experience this black body. Just because I was born into this doesn’t necessarily mean that I claim it as my identity. However, showing these images is also reiterating a structure that people want to pacify. It’s like, ‘No, we can’t see this because it’s too painful.’ We triggered a sense of trauma in him. And I can understand why he believes that we shouldn’t, but it’s to make him feel comfortable and safe.”

But can black people make art that is devoid from racial context?

“To control the narrative fully, we have to know about the lighting, we have to know about the music, and we have to know about the entrance…” Gray finished.

Stay tuned to InTheRough for more developments on Uptown Art House’s theatrical productions headed into 2019.