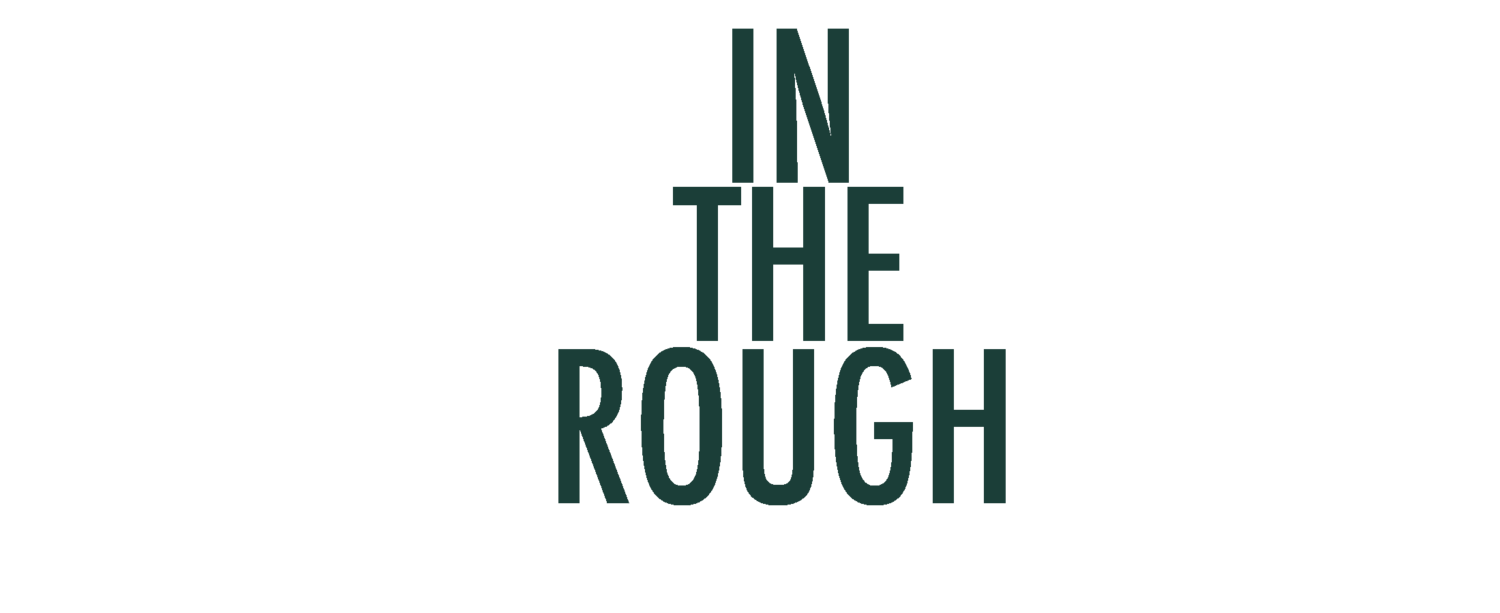

A curious hotel guest listens to the first Uptown Cypher of 2020. Polaroid by Maxwell Young, The LINE Hotel, 1/29/20

‘Uptown Cypher to the main stage. Uptown Cypher to the main stage, it’s showtime,’ a sound engineer’s Walkie-talkie growls under the stirring crowd as stage crews prepare for opening curtain. At least, this is how I imagine Saturday’s show at Comet Ping Pong; the Cypher sharing the spotlight with boisterous ambassadors of D.C.’s rap conglomerate in Wifigawd and Odd Mojo, while Medhane’s shooting star passes through District limits. Hip hop in its most instinctive and communal moments juxtaposed with the more compositional and performative elements of the genre—this is an experiment controlled by Angelie Benn, founder and lead events director of Capitol Sound D.C.

“Including interactive performances at [Capitol Sound] events has been on my agenda since last year, but I rarely ever saw an opportunity to do so where it made sense,” Benn said over email. “Now, with the Uptown Cypher a part of this lineup, it furthers our mission of building the bridge between local and national acts…”

Throughout 14 episodes broadcast via the home base of Full Service Radio, the Uptown Cypher has served as a public service announcement, amplifying the myriad of sonic pockets evident in the DMV’s hip hop community: the street sense of MARTYHEEMCHERRY, Fleetwood Deville, Paydroo and SQ; the esoteric consciousness of Mavi, Thraxx King, NAPPYNAPPA and Nate G; the head cranking brought to you by Discipline 99, Johnny Caravaggio, Mfundishi, Supa Statiq, Suede Moccasins and Magnus Andretti; contemporary bops by Cozi Bob, Mesenfants Infinity, Tedy Brewski, Odd Mojo, Khan and Toothchoir; fundamental soul from legends YU, Fat Kneel and Thrty Smthng; the effervescent Greenss; backpack licks from Flex Matthews, Rafael, Nate Jackson Kills Niggas and Paris; the brand name presence from THFCTRY and Sir E.U—Andrew of ROOMHAUS and his necessary warmup mixes. More than 60 locally-based vocalists, emcees and producers have taken the pilgrimage to The LINE Hotel to expand the reach of the DMV sound. For hip hop heads young and old, for the rookies and the veterans, the Uptown Cypher is a platform for artists to hone their skills live and direct, on air. Ultimately, it’s an archive of the District’s musical ecosystem.

Thanks to the one-night triumvirate between InTheRough, Capitol Sound D.C. and Uptown Arthouse, we are proud to present a sampling of the Uptown Cypher program. While we invite all willing wordsmiths and beat-makers to participate, Saturday’s session will be kicked off by longtime friends of the Uptown Cypher, including Nate G, Greenss, Thraxx King, MARTYHEEMCHERRY and Master of Ceremony Jamal Gray. Tickets to this weekend’s show are available here.

The Uptown Cypher is broadcast live via FullServiceRadio.org from 7-9 PM, EST on the last Wednesday of every month. Listen to the one-year anniversary Cypher or the first Cypher of 2020 below.

Uptown cypher

March 7, 2020

10pm-1am

5037 Connecticut Avenue, NW

Washington, D.C., 20008

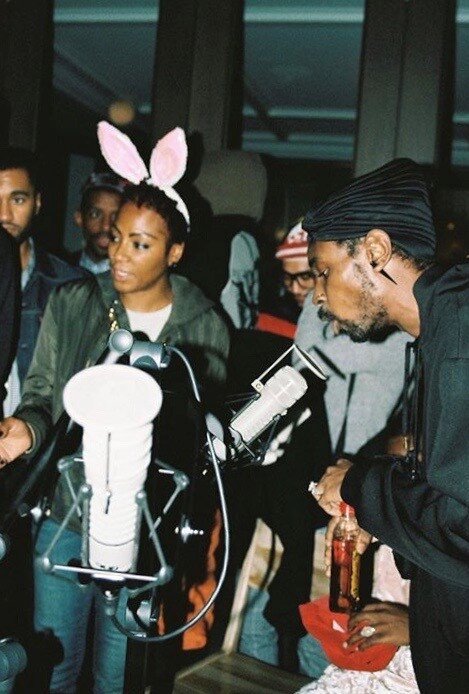

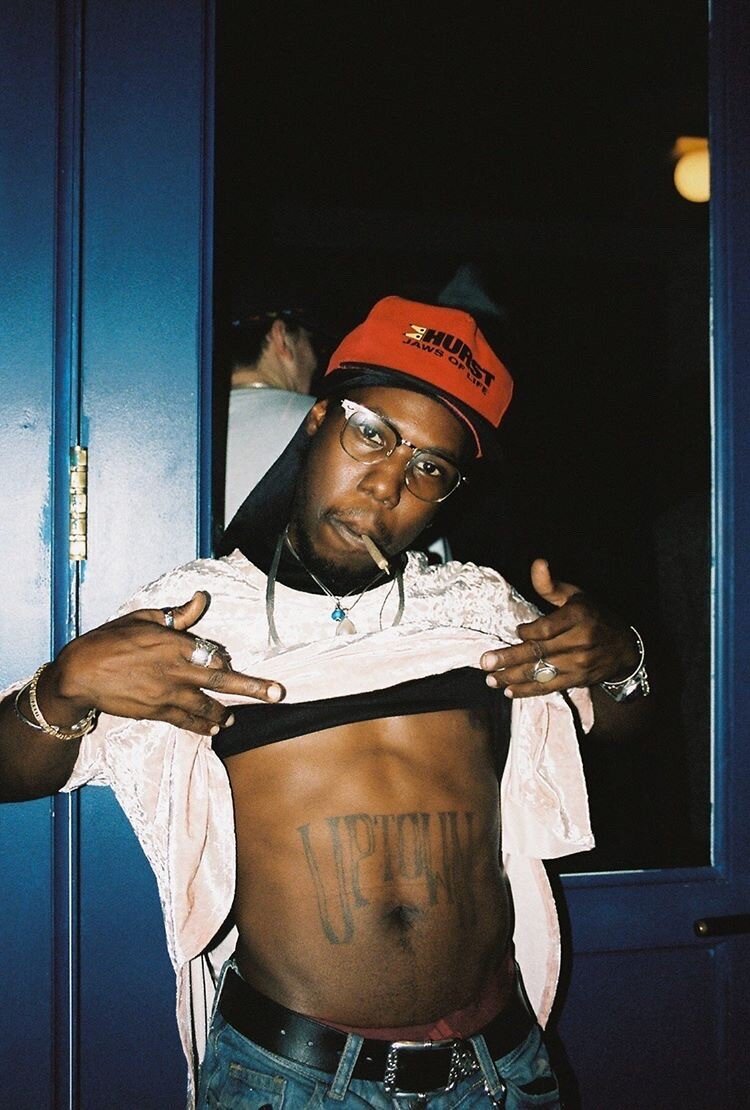

Carousel images from the one year anniversary episode of the Uptown Cypher, courtesy of Diana N.