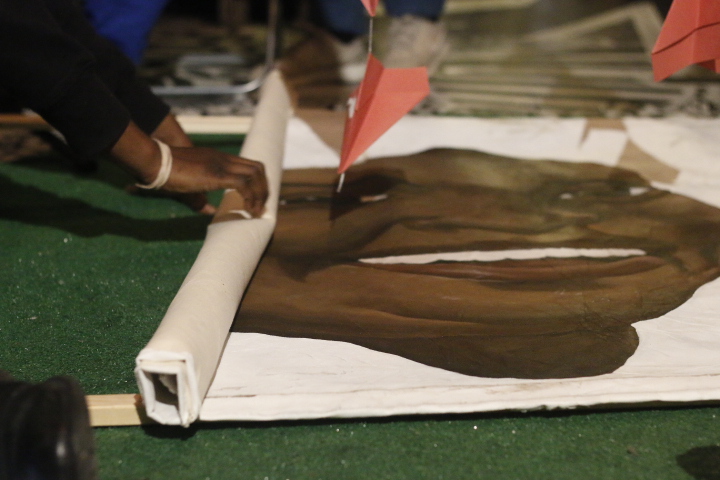

Elijah WIlliamson stitches back ripped canvas of his “Aunt Jemima” portrait, Black Dove. Photographs by Ashley Llanes

What do you do when the oil portrait you’ve worked on for a year falls out of the back of a pickup truck, onto the highway, and rolled over by oncoming traffic?

For artist Elijah Williamson, that moment was just the beginning of a beautiful journey to his installation, Black Dove at Maps Glover’s exhibition, What We Leave Behind: In the Name of Art—a six week endeavor that ended October 20 at Washington, D.C.’s Transformer Gallery.

Black Dove is a portrayal of “Aunt Jemima,” the matronly or mammy-figured black woman synonymous with thick, fluffy pancake batter and sugary syrup sold in any non-organic supermarket.

“She,” as Williamson refers to his work, has an overwhelming pureness to her composition. Jemima’s classic bonnet, usually plaid, is painted white while her brown face is bordered by more strokes of white, creating a stark contrast between light and dark. The ear was a main focal point for the Corcoran College of Art and Design graduate. In the decades that Aunt Jemima’s packaging has evolved, her ears have been omitted—stripped down perhaps for lack of necessity. It’s as if Williamson plucked this logo from his syrup bottle stashed in the cupboard and humanized “Aunt Jemima,” aggrandizing the black existences of Nancy Green & Anna Harrington whose likeness were manipulated by The Quaker Oats Company.

When you consider this exploitation—the allusion of Southern hospitality brought to you by the hot fixings of your loving ex-slave/negro cook—the rips, smudges, and tatters of the canvas, in a way, seem more fitting for a final piece than the clean, idyllic image Williamson had originally foreseen.

The commercial graphic designer spent the afternoon and evening of Glover’s final Saturday service in October stitching together the torn parts of canvas and re-stapling the composition back to a wooden frame. It was ceremonious as bystanders helped to hold the frame in place. During one moment, Williamson sang Sam Cooke’s “A Change Gon’ Come,” eliciting feelings of an antebellum period.

He reflected on this traumatic journey via email:

InTheRough: Working on a painting for a year takes a lot a of persistence. I find the endeavor interesting because I don't know you as a fine artist. I know you as a graphic designer. What was the impetus behind your undertaking?

Elijah WIlliamson: Yea it’s crazy, I’m actually a fine artist turned graphic designer. When I told one of my drawing instructors in college that I was a GD major, he responded,“I don’t know. I think you may be selling yourself short for a paycheck.” I’ve never forgotten that moment but now that I think about it, I’ve always found a way to marry the two.

For this piece however, it started as a response to my senior thesis project at the Corcoran College of Art and Design at George Washington University. I was investigating pieces of graphic design created during the Harlem Renaissance and was struck by the differences in how Black Americans were portrayed depending on the artist demographic. I came across a number of stereotypes cast upon the African American community; the first was the “mammy” caricature. I began drawing sketches of Aunt Jemima and around that time, there was an ongoing lawsuit around royalties and proper compensation to the women who reportedly spearheading the morning and then it fed this brand. The story was all too familiar, yet ironic at the same time.

Visually, it struck me that the representation of Aunt Jemima was never depicted with an ear. I also learned that the character was inspired by a song written by a black minstrel performer. These things coupled with other readings and conversations around Black women in America, I wanted to contribute something that attempted to fill the gaps created by negative stereotypes of black women. I also wanted to contribute to the commentary of costume. It was important for me to remove the headscarf. In so many ways it represented nothing of personal note. It was utility, almost costume. I wanted to challenge the visual perception of how we see “Aunt Jemima”, who for a long time, is how Black women are viewed in America.

It took a year to complete for a number of reasons, the main being my constant attempt to juggle a full schedule but mainly, I wanted to take my time. I was creating other Jemima pieces and I wanted the series to grow and express itself over time. Different portraits went in different directions and meant different things.

ITR: Walk me through the moments after your painting fell out of the truck. How do you rebound from that experience?

EW: Ah.. wow. I had a buddy of mine help me transport it from my place in Virginia to the Gallery. I was constantly turning my head to make sure things were good. One moment it was there, the next it was gone. We pulled over and I immediately took off running back up the shoulder of 395 against traffic. I ran maybe a quarter mile before I saw the piece on the ground, off the stretcher, being ran over by traffic. I remember hearing the wood rolling against the asphalt as it was hit by the rubber of rolling tires and the crashing of vehicles against the canvas. I screamed, “No!”. I was waving my hands trying to stop the traffic until I was able to retrieve the canvas as the cars responded to my hysterics on the side of the highway. After I quickly gathered the remains of what was left of my piece, I headed back up 395 to find the truck. I remember taking a breath on the guard rails on the side of the road and thinking, “What The Fuck!?”

It really was the support and encouragement of my close friends who, in a way, carried me through that experience. I was in a state of shock for some time and really didn’t want to discuss the incident. There were a number of other factors going on that weren’t exactly encouraging. My name was omitted from the list of artist on the first set of postcards for the show, and Maps Glover, my best friend and curator of the show, had been having concerns about whether the exhibition was the right show for this piece. Needless to say, I wanted to drop out of the show. I was pretty shook. A lot of emotions were at blows with each other; shock, anger, pain, wasted time, shame, embarrassment - it was rough. We didn’t know how it was going to work, but I had already been compensated and made the commitment. It was a horrible situation to be in. But we pressed on. The opening was that weekend and it was a hit. My performance wasn’t scheduled for another six weeks. I don’t think I was able to really move pass the fall until the day of my performance. It was still fresh - for me - up until that day.

ITR: How did you arrive at the idea for your performance, which closed out Transformer Gallery?

EW: That performance was about as organic as it gets. I knew I wanted it to be interactive and I wanted to engage the audience. Outside of that it was just about telling the story in a way that was as complete and authentic as necessary. It wasn’t lost on me that this “feminist attempt to present a whole image of black woman” was being lead by a black man. In an effort to subdue myself in light of the content, I chose to have excerpts from the artist statement read aloud by the participants of the show.

Visitors at Transformer Gallery helped Williamson reframe his painting. Photograph by Ashley Llanes

These excerpts were taken from the Combahee River Collective Statement. A document written by a group of black feminist and lesbians responsible for one of the first introductions of intersectionality into political and social conversations. The name, ‘The Combahee River Collective’, refers to the Combahee River Raid - an expedition of 150 Union Troops lead by Harriet Tubman. The raid lead to the destruction of several South Carolina Estates and plantations. Harriett Tubman is the only woman known to have led a military operation during the American Civil War.

ITR: What songs were you singing? I was eating, so I only heard. Your portrait and your voice transported me back to slave times, especially looking at the images Ashley caught of you sewing it back together. It truly was a spiritual moment. Jemima plays this mammy role and to be canonized in an iconic brand image is very much exploitative.

EW: Yes it is. And the act of revealing that kind of exploitation was what I was trying to execute; exposing this disenfranchisement towards Black Americans, specifically, Black American women—and that does date back to slavery.

The song I sang was ‘A Change Gon’ Come’ by Sam Cooke. It had been with me for a few days that week and it just made sense to perform it. The lyrics really captured a part of what I was trying to say in relation to the subject matter.

ITR: Watching you perform all of these exercises around the portrait: sewing it together, framing it, and celebrating it--the whole experience seems like that's how it was supposed to happen. How do you feel removed the experience?

EW: It’s still pretty surreal. From like the fall to the stretching. I do find a lot of symbolism in the different phases she [the painting] went through. I don’t know if it was ‘supposed’ to happen like that (laugh). But I do believe what happened happened for a reason. I’ve definitely learned a lot from the experience as a whole. I’m extremely grateful, man. It was quite the journey but I’m glad I stuck through it.

ITR: What’s next?

EW: Right now I’m getting settled in DC. Moving in the district will be a big move for me. I’m still painting. I want to get through this series.