Alex Young: What is the genesis of Kamili?

Amani Davis: I feel like in College motherf*ckers work too much... In Organic [chemistry] class you're looking at shapes of carbon--carbon makes little shapes: hexagons, triangles, all this little sh*t. I was looking at it and I knew it was an abstraction. I might have solved these problems, but even if they tell me I got an A I still don't know how this sh*t works. I was studying and I worked really hard all summer, studying, studying, studying like a little b*tch. And then there was this little piece of wood and I was like Mom I'm gonna paint on that. I painted this stupid thing but to me it's like, "Oh I learned all this stuff and it's coming out in this stupid painting," and you just forget it. It's kind of a sad view of school, but I'm glad I know that sh*t obviously. I think I realized painting whether you are good or bad at it is definitely therapeutic.

Hannibal Hopson: I can definitely second that thought about painting being therapeutic, one, and two just the way that I had come about it. What initially was kind of a thing I had done when I was really young I didn’t really know how to… I was trying too hard. I was looking at images in my head and I wanted to duplicate those images. I sat here for two days on the porch and I just started drawing on the inside of a desk. I started drawing on it and I painted it a bit and then all of my ideas started flooding in terms of what else I wanted to do with this time and space... I immediately started writing a ton more, I started reading more just so that more thoughts were going through my head, there was more inspiration, I was reading different types of things, I was reading different authors, and I was making music again. It was kind of a culmination and painting was the tale end of that culmination of real rejuvenation.

Amani: I was talking to a friend of mine today and he was like, "All you can do is hope that your art is tight because no one is going to tell you if it sucks or not." If it's garbage, it's garbage and you'll really never know. Your mom is going to be like, "Yeah it was tight." There was a moment for me looking at my shit being like 'its all garbage' to 'wow I kind of like one or two of these things.'

Alex: How do you feel about the lack of honesty, people not being honest about art?

Amani: That's the thing; most art right now is bad anyway. I don't want to say most art is bad, but I think a lot of artists rely on interpretations.

Hannibal: Art is so broad nowadays; it covers so many spectrums of our daily lives. I like to think that we each have our individual creativity and definitely a side you can tap into. Artists recognize artists not really grasping the basic fundamental parts of art: being in tune with yourself, trying to figure out some of the things that you are thinking or dreaming and how to put that on paper.

Amani: A lot of it is about interpretation, how does one present themselves in reference to their art and make statements about their art... its way different than all that museum sh*t.

Hannibal: Unfortunately right now the hip hop industry is glorifying drugs and how drugs affect art and it's just kind of like is it really making you a better artist or did you always have that capability.

Amani: My favorite artist is addicted to lean.

Hannibal: We still bump Thugger (Young Thug) like whatever, we definitely respect his artistry.

Amani: I put my Mom on Thug. If the only way you can rap is by being high as fuck off lean then do it, but you don’t have to sell it to my little brother man, he’s little.

Hannibal: I’m reading a Basquiat book about his drug use. It’s a biography, but obviously if you want to talk about Basquiat then you have to talk about New York in the ‘70s, ‘80s, club culture, new fashion, new disco, new law. This is a very changed world for artists in New York City and Manhattan. Basquiat was doing drugs in middle school and he never said anything about it, he never came out. People knew about it, he might have said one time I was high whatever, smoking on some grass whatever, but when it came down to it, it definitely ruined him in the end, you know he died of an overdose, but that’s something he did in his personal life.

Kamili is commemorative because it is authentic--it literally draws upon the material, which has long since been erased. The harsh reality of Pittsburgh's concrete jungle is change is ever-present, making gentrification and commercial re-development frequent across the city. Amani and Hannibal have seen their East Liberty, Pittsburgh neighborhood shift and commercialization remove the area's longstanding culture. As a result both artists deliver a tangible and organic exhibition to remember the community that raised them.

Alex: What is Kamili a commentary on?

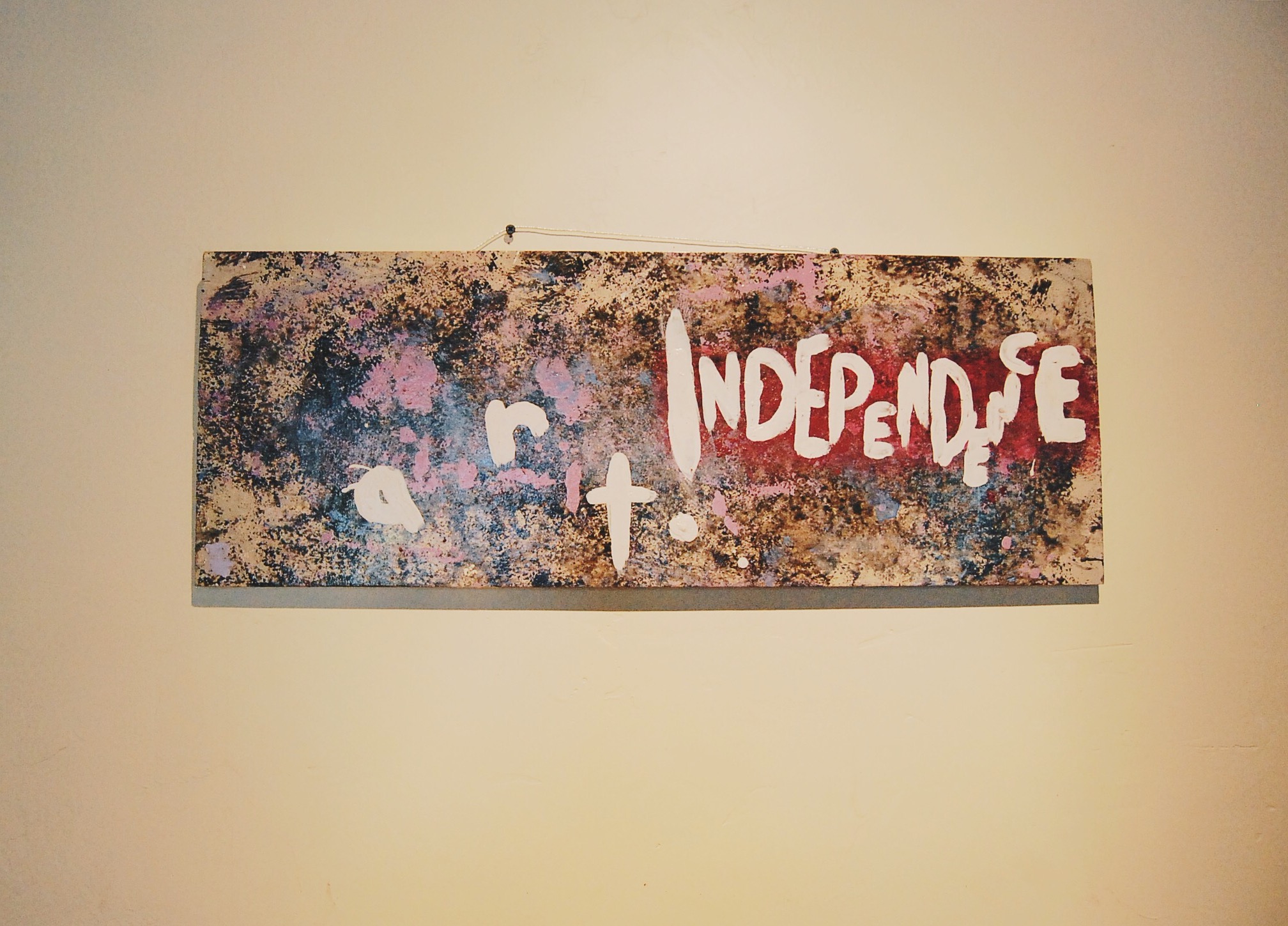

Amani: To me if there's anything that I hope anyone goes to the show and f*cks with I feel like that wood was the art, that piece of garbage that someone threw out from someone's house and motherf*ckers were forcibly moving people out of homes through police, through money, or through gentrification-- all that bullsh*t-- that someone threw out a piece of someone's home that no one gave a f*ck about. I took time with it, I wanted to love the wood so motherf*ckers would be like, "Yeah people used to live here, people still live here, and I want to know where the people who lived there live now,"... the meaning is not on the art, the meaning is the wood.

Hannibal: The fact that you can't park on my street and my street will get permit parking in the next 5 years just because we have random people who are going to school at Chatham University just parking on our streets... that's something we can't really grasp, but we can grasp the people who have moved out of these homes.

Alex: How does sustainable art fit into this situation?

Hannibal: When you talk about sustainability and when you talk about art... there is a difference between what we are doing and street art. When you think about commissioned street art that is an element of sustainability when you can take a defaced property, when you can take a retaining wall and put someone who is artistically minded and go, "Here, please make this look a little better than it is," that's sustainable thinking. I speak to the clutter kind of piling up on each other so we gotta figure out ways, how can we limit, or how can we reduce, reuse, recycle-- the three 'Rs'-- how can we R and R and R our world.

Amani: I think with this there isn't that sense of pride with the residents of a neighborhood because that's just people. When those people leave, the space is still the same, but the space is very different now. I would not go to a block party in my neighborhood now, when I may have four years ago... I really hope that someone might say that this is street art, it is definitely about my street. My street is a different f*cking street now, but that sh*t in that room (referring to their art pieces), that's the street, that's the street that I seek to remember. Gentrification is crazy. There's no outlet to be like, "You know what, that's f*cked up. Where the f*ck do these people live now?" Obviously there's a positive way, an angry way, an ignorant ass way to do it, and a respectful way to do it, but I think that's something that motherf*ckers do not talk about. It's so linked to police brutality, incarceration, and all these problems. All these f*cking yups go home in their homes and are like, "Oh yeah that's so crazy that happened." It's like no, one you don't know and two, you're exacerbating this... I wasn't angry the whole time we were doing this I was having a ball.

Hannibal: No, there are definitely moments of anger. There are definitely moments where I have been angry in painting and there are definitely pieces that will be in the show where there's anger while I was painting and a lot of it had some very serious stuff to do with it. But the painting process itself wasn't necessarily an angry one, it was always a fulfilling one, it was always a relief.

Amani: This space is always going to be East Liberty… when neighborhoods flip socioeconomically in terms of the whole community, I feel like people want to forget sh*t.

Hannibal: That’s why they knock down schools.

Amani: Yeah, that’s why they knock down schools, change names, and shit. At least Hannibal and I are going to know other motherf*ckers lived here as well.

Hannibal: My Pittsburgh high school experience I can’t go back to either one of the high schools. One is being turned into apartments and the other one is already apartments and then knocked down. There is a whole class of Pittsburgh students who don’t know where we are going to have our reunions.

Alex: Would you say gentrification is rampant in Pittsburgh?

Hannibal: No, I would say the culture in Pittsburgh is one of inclusivity in terms of grasping to your neighborhood, grasping to family because Pittsburgh has that small town feel… I would say not gentrification, but definitely an attachment to your home, an attachment to your neighborhood, an attachment to the people around you, an attachment to childhood memories if you want to put it like that, but definitely space, we have that, neighborhood kids going to neighborhood schools—we have that. So if you knock down a school…?

Amani: Ya what the f*ck is that...

Hannibal: Obviously there are factors that you can't really weigh into or whatever, but that’s definitely something that has inspired our art and that is definitely something that we can speak to about our art… I don’t even want to make it a gentrification thing; I feel like even that is a cop out because there are factors that lead to gentrification. But, I will definitely say that the neighborhood aspect, especially in a city like Pittsburgh, is important. Being able to stay in your neighborhood and catch the bus, that’s why with the bus cuts everyone was hooting and hollering because people would have to walk outside of their comfort zone and there weren’t enough buses. Realistically how were they going to do that? And that’s when they decided they weren’t going to cut all the lines, but a small fraction. That stuff is important.

Amani: If your art sucks, not if your art sucks, but if people can’t find either meaning or just raw aestheticism then you probably missed the mark. I hope that if our message is received that people do realize that we are two black guys who did some cool sh*t about their neighborhood.

Hannibal: Real deal Holyfield these are pretty raw emotions… we are talking about organic experiences. You don’t have to go above and beyond your comfort zone to have organic feelings. The whole point of the art is that it’s always inside of you.

Go see Kamili for yourself in its last day at PointBreezeway today from 6-9pm.

PointBreezeway

7113 Reynolds St.

Pittsburgh, PA 15208