Bid to Fight COVID

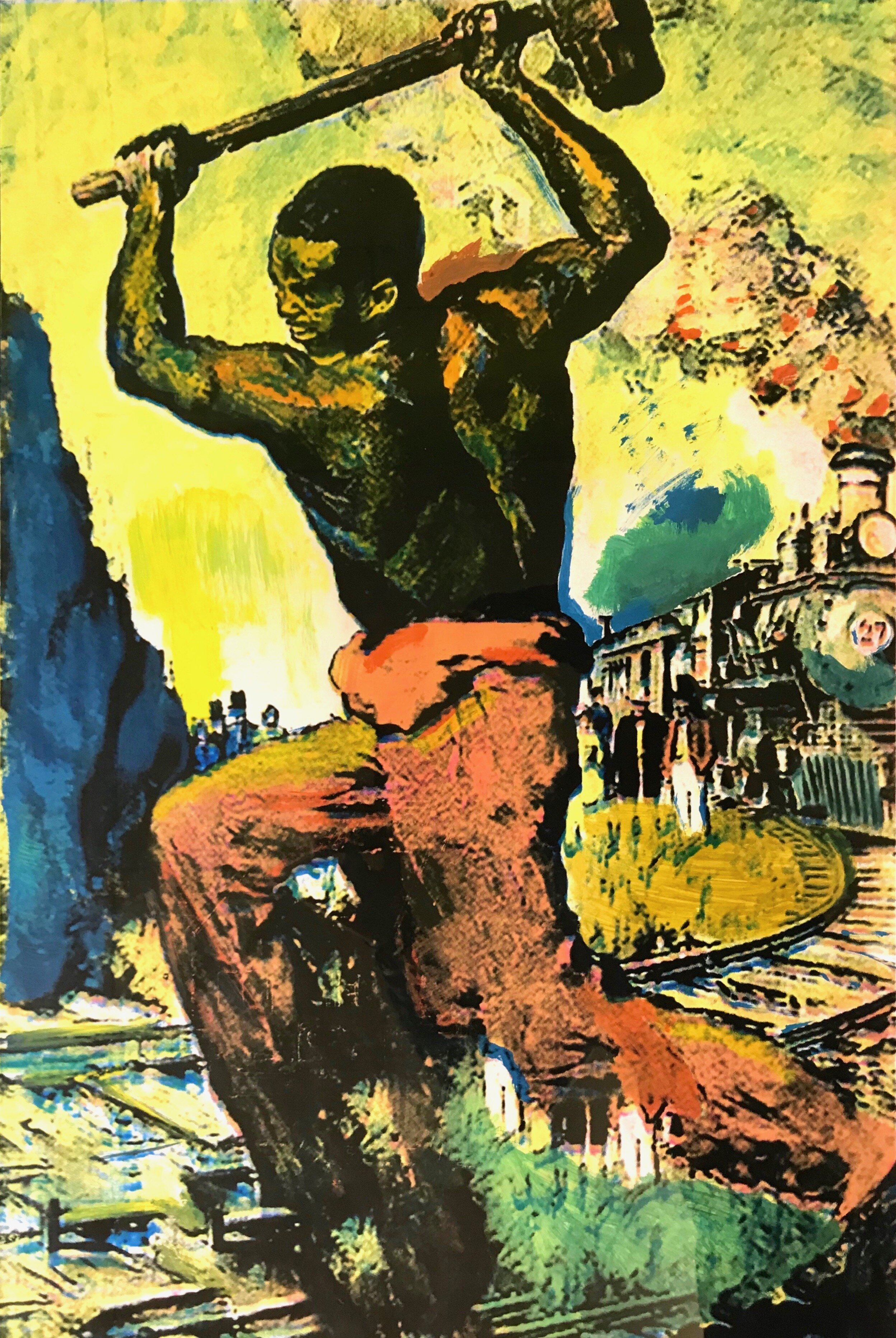

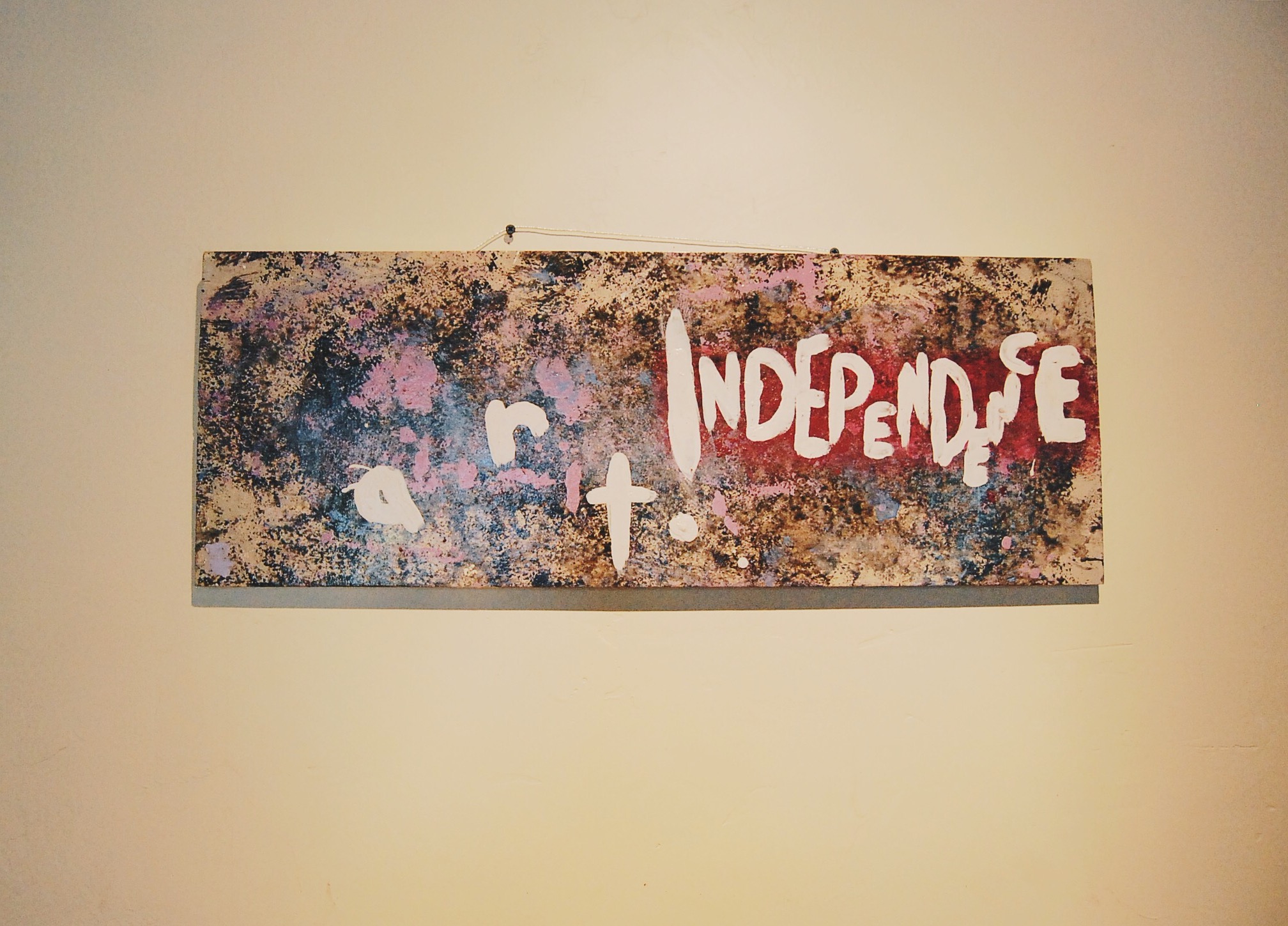

“John Henry” by Quaishawn Whitlock, Bid to Fight COVID logo & “Platinum Club” by Hannibal Hopson

It would be easy for despair to invade minds right now. The pandemic set siege on our social lives and some jobs. Black men and women fall, murdered by police live on the Internet. You think it will stop, or when there hasn’t been a case of fatal racism broadcasted for a while, you think the human climate is better. You were wrong. You get a therapist for your P.T.S.D. that this whole ordeal causes you subconsciously amidst the other shit flying towards you in life— perhaps a bullet from a mass shooting or an ex-lover giving you angst. A good therapist might tell you not to dwell on the emotion and pain, but use it in action as you progress. So, you focus on other things that make living worth it, like art.

“Historically, art has played a pivotal role in improving the public welfare during adverse periods,” Maxwell Young wrote in the summary of Bid to Fight COVID, an online art auction where the proceeds support 21 artists from D.C. and two from Pittsburgh, along with Martha’s Table— a non-profit building community through education, food and opportunity.

The Pittsburgh native artists among the cast of D.M.V. talent in the auction are Hannibal Hopson and Quaishawn Whitlock.

“Art articulates longing and belonging, an act that signifies and indexes the displacement and disorientation of the lived experience, acting as a compass for societies to transform themselves through the process of digestion and expression of the suffering and triumphs of communities,” Hopson said explaining art’s responsibility to humanity.

The intrinsic value of art becomes apparent when a piece captures and grounds life’s intangible beauty that resonates with everyone in some form or another. To own that or have that feeling hanging on your wall is an entire phenomenon in itself, which is a true privilege. “When buying and collecting artwork either from a particular person, time, or style - that individual is investing into that conversation and sharing amongst others who experience the artwork,” Whitlock said.

Bid to Fight COVID T-shirts | Photos by Maxwell Young

On Friday, May 29, grab the chance to win lot number six, “Platinum Club” by Hannibal Hopson (5” x 21” acrylic on canvas), or lot number 11, “John Henry” by Quaishawn Whitlock (22'“ x 30” CMYK screen print on paper), during the Bid to Fight COVID auction via Instagram Live at (@bid2fightcovid) or Zoom call (meeting ID 836 5734 1750 & phone hotlines 646-558-8656 or 301-715-8592) from 7 p.m. - 10 p.m. You can still register for the auction here. Participants can also enter a raffle to win buttons made by some of the artists in the auction, or souvenir Bid to Fight COVID T-Shirts printed by Maxwell Young and Quaishawn Whitlock.

Both Hopson and Whitlock shared their thoughts in interviews below about how the pandemic impacts art, as well as the value in buying and collecting art.

Register to Bid to Fight COVID. Register to Bid to Fight COVID. Register to Bid to Fight COVID.

“Platinum Club”

Interview with the artist Hannibal Hopson

ITR: What is art’s role during times of hardship and how are you fulfilling that?

Hopson: Art articulates longing and belonging, an act that signifies and indexes the displacement and disorientation of the lived experience, acting as a compass for societies to transform themselves through the process of digestion and expression of the suffering and triumphs of communities. Art has always played a very vital role during times of adversity and distress. For artists and creators, hardship challenges us to tap into our core innerstanding of what no longer matters, what needs to be destroyed, what needs to be made and who needs it the most. For observers and collectors, art translates the story of life, reminding people where they are and what they need to remember about themselves and the world around them at any given time.

Most of the world's greatest social/political movements were birthed during times of distress. From a Western Contemporary lens, when we acknowledge the Great Depression and WWII as significant global shifts, we also recognize 1) the impact of the New Deal, which led to the expansion of community art centers, public murals, and artist collectives in America, and 2) the genocide of non-Aryan people and desecration of “degenerate art” by Nazi Germany, launching the post-war scramble for old masters and emergence of the NYC art market. Some of the most notable and influential Western artists and art forms were products of this time period and in its aftermath, of which the value of the names, works, and movements speak for themselves in today’s art market.

Personally, I am currently quarantined in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. Although I have come in contact with an incredible space for art and artists here, really what I have found is a very striking challenge and opportunity to iterate my own existence away from a densely human populated area and submerge myself within my own true nature, breathing with the Earth. My role within art during this time is to share my story and the essence of my being as I unearth reactive frequencies and make way for a more proactive me.

ITR: How has the pandemic impacted how you create art or sustain yourself through art?

Hopson: In my isolation I have asked myself, ‘why must i create’? The answer that was revealed to me was simple and resounding: ‘because you are living’. It is clear to me that every living thing in nature must create and sustains itself through its own reaffirmation of being. Every season brings change, the only way we know that change exists is because we are around long enough to change also.

I have been fasting from vibrations that do not bring about a positive light within me. My focus and intention is to share the essential characteristics of my purest self through creation, offering my heart--light and love--from the communities I embody around the world that emanate from my person. I have been studying the simplicity of village life and the collaborative energies that are mobilized in close knit connections through action or inaction.

ITR: What’s the value in buying/collecting art?

Hopson: I always like to think that there are moments, at your family dinner table, in your bathroom, or in your bedroom, where anything is possible and everything happens and changes. At the same time, the art in your environment is undisturbed and immersed in the present moment. You may enjoy the moment or you may destroy the moment, however the art is always the moment itself. I encourage embracing and investing in your own moments, whether good or bad.

Art, as a repository of cultural memories that represents a collective archive of being for all humans, transcends time and space. This means that something that you create today may have more value to you than it would 30 years from now, or vice versa.

When it comes to buying and collecting visual art (performance, culinary and written art are slightly different), there are a few unique qualities that generate its value as a commodity. Visual art serves as medium of exchange, a store of value, it is scarce, you cannot double sell the same piece (only one person or entity can ‘possess’ an original work of art at any time), and it has a distinguished provenance (the art value is generated and chronologically recorded from its inception as a legal track record, or ledger, of proprietary ownership) similar to a home or a vehicle. These are important aspects of the value of visual art because like other commodities, the market value is regulated by the fixed, finite supply of work in the market and its liquidity is protected by market appraisal.

In today’s economy, visual art as a commodity of exchange can be great for an artist to generate revenue, or terrible for an artist if the market were to devalue works not championed as exchange or investment commodities, especially in the age of mass entertainment and mechanical reproduction (see Walter Benjamin), remixing and cultural appropriation.

ITR: What do you hope to get back to once life returns to normalcy?

Hopson: I am a wanderlust. I love traveling and visiting my friends around the world. I enjoy dancing, celebrating and connecting with others without fear. The nature of COVID-19 and the problematic jargon of “social distancing” is that it has encouraged a world of social agreement extremes. I feel that trust is even more at stake with every encounter now as we hold more social responsibility for others’ safety in a physical manner. The masculine electric energy source within me is reminded of moments in which I had taken space between myself and others for granted. Now I feel a heightened level of feminine magnetic energy that will repel as much as it attracts, unwilling to connect if the frequencies aren’t divine. What’s normal again?

“John Henry”

Interview with the artist Quaishawn Whitlock

ITR: What’s the value in buying/collecting art?

Whitlock: Artwork can be a vehicle to communicate across almost every platform available. I believe when buying and collecting artwork either from a particular person, time, or style - that individual is investing into that conversation and sharing amongst others who experience the artwork.

ITR: Talk about John Henry as an icon

Whitlock: John Henry is/was a manifestation and experiment of how these stories can be woven into both my work but my practice as a whole. Some heard or read the story growing up - The freed slave who was one of the best railroad drivers of the time period. Over time and tales of the folk hero/man who raced against the steam engine to keep his job.